Welcome to the "New Hope Creek Biodiversity Survey 2021- 2022" website! |

|

Special thanks to our partners: | ||

|

|

|

About the NCBP.

The North Carolina Biodiversity Project (NCBP) is a private, non-profit association devoted to gathering and sharing information on the state’s native species, habitats, and ecosystems. Our aim is to support the understanding and appreciation for biodiversity in all its varied glory. We currently have 14 websites and six additional checklists representing all four of the kingdoms of Eukaryotic organisms, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. If experts on the Prokaryotes have an interest in joining our efforts, we will be more than glad to add the Bacteria and Archaea to our coverage. The list of our individual taxonomic projects, along with a detailed description of our mission, can be found at the North Carolina Biodiversity Project Website.

Our work focuses primarily on the creation and management of these websites, which make detailed information on the state’s biodiversity freely, easily, and widely available. However, we are not completely desk-bound; we also play a key role in gathering the information that goes into them. Our members are proud to call themselves field biologists, nature photographers, or naturalists in general. We like nothing better than getting outside –braving the elements, high water, steep terrain, and other rough field conditions – in order to document new species to the state or to better understand the distribution, abundance, habitat associations, and other aspects of natural history of even our most familiar species.

Our intention as an organization is to be directly involved in all aspects of biodiversity investigation. In this regard, the New Hope Creek Biodiversity Survey provides a model. All of our website groups are taking part in the field work and the website you are currently viewing is our characteristic way of sharing this information far and wide.

About the New Hope Creek Survey.

Durham County, along with many other governmental and private organizations, uses information from biological field surveys to help guide land use planning and conservation efforts. Durham, in particular, has long used surveys conducted under the auspices of the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, Durham County Inventory Review Committee, and Triangle Land Conservancy (Sutter, 1987; Hall, 1995; Hall et al., 1999) to determine what areas to protect as natural areas, to include in reviews of potential impacts of infrastructure projects, and to help guide development plans more generally. Several tracts along New Hope Creek, between protected natural areas in Duke Forest and the New Hope Game Land were acquired by the county as part of this process.

The natural area surveys in Durham County, however, were among the first done in the state and they are now long out of date. Given the great increase in development that has taken place in Durham County over the past several decades, along with other environmental changes such as those due to climate change and the arrival of invasive, exotic species, the continued presence of many of our native species is now in doubt. So is the quality of many of the natural areas identified as having high conservation value in the earlier reports. Moreover, views about how to best conserve our native species and ecosystems has evolved over the past decades, giving more emphasis to ecosystem and landscape-level considerations rather than just quality of individual sites and the imperilment of individual species. Equally important, there is now a realization that different groups of organisms can react very differently to environmental change. Each group can provide a unique evaluation of habitat quality and each may have very different needs with regard to conservation and management.

In 2021, the Durham Open Space Program applied for a grant from Burt’s Bees to conduct a new biological field survey of the bottomlands along New Hope Creek, focusing on the tracts previously acquired by the County but also including adjoining lands that are currently not under conservation protection (see Maps on the menu bar for illustrations of the study area). Rather than just repeating the earlier surveys, however -- focusing on the same groups of species – this survey proposes to document a much wider array of taxonomic groups and a greater number of species. These include common species that are relatively secure, as well as those that are rare and at high risk of local extirpation. They also include groups of species that are well-known to the general public and whose conservation is generally supported. Additionally, poorly-known or widely misunderstood groups – e.g., Spiders, Myriapods, Fungi and Slime Molds -- are included in this survey in recognition of the important ecological roles they play. These are also groups whose conservation needs are usually ignored or overlooked, assuming – with little to no evidence – that whatever is good for the better-known taxa will be sufficient for them as well. Such assumptions are not safe to make and neglecting these taxa results in the failure to take advantage of the different picture they can provide of site and ecosystem integrity.

Assessments of habitat and ecosystem integrity are themselves key goals of this survey. As in the earlier surveys, the priority for conservation of the individual tracts of land included in this survey will be a focus. Equally or even more important, however, this survey will look for evidence that New Hope Creek Bottomlands plays a keystone role in maintaining the landscape integrity of the entire region: are these tracts used by species that are highly vulnerable to the effects of habitat fragmentation and do they connect populations of these species up and downstream from the study area?

To conduct this multi-taxa, multi-faceted survey, the North Carolina Biodiversity Project was subsequently contracted by the Durham Open Space Program. This is a project that the NCBP is particularly well suited to perform. Not only does the taxonomic expertise of our members span four of six Kingdoms of organisms -- all of the taxonomic groups currently included in our website projects will be targeted for this inventory -- but this survey itself exemplifies our interest in the direct gathering of data on species, habitats, and ecosystems and the use of this information to raise public interest and support for the conservation of these entities. All of our members have great expertise in searching for and identifying species in their taxonomic specialists. In many cases, they also have had decades of experience in determining the ecological associations of their species and in assessing their conservation priorities and management needs. As demonstrated by this current website, we have also had a long history of making the information widely available to a variety of conservation and scientific partners, including the general public.

This survey will focus on the terrestrial and wetland taxa of the New Hope Creek bottomlands. These include Mammals, Birds, Herps, Bees, Moths and Butterflies, Beetles, Hemipteran Hoppers, Orthopterans, Odonates, Arachnids, Myriapods, Vascular Plants, Bryophytes, Fungi, Lichens, Algae, and Slime Molds. Field work will be conducted over an entire year, with surveys for each taxonomic group timed to sample the maximum number of species within their taxonomic specialty. Sampling will be done primarily by members of the NCBP but will also involve contributions from some of our partners. At least a few public bioblitzes are also being planned and individual contributions to this survey via submissions to our multiple websites will be highly welcomed (see information under Public Involvement on the homepage menu).

The final report for this project – due in October, 2022 – will summarize our findings both for the taxonomic groups included in the study and for the habitats they occupy. These two perspectives will combine to provide recommendations for further conservation efforts. These will focus not only on land use planning and management efforts to protect the immediate project area but also on preserving or enhancing the functions the bottomlands serve in maintaining the viability of native species throughout the natural areas linked by the New Hope Creek corridor.

Location and Extent

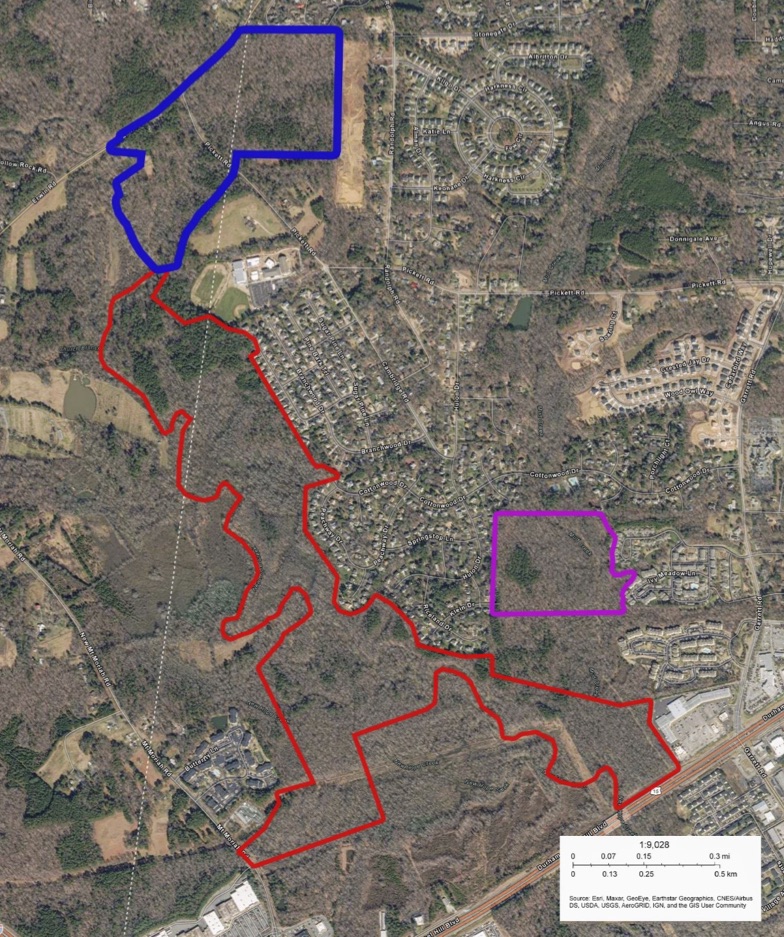

The area included in the survey is shown in Figure 1. The northern, upstream boundary of the study area is Erwin Road, with the Korstian Division of Duke Forest lying directly to the north. The southern, downstream end is Old Chapel Hill Road, which has tracts of the New Hope Game Land on both sides of the road. The outline shown on this map corresponds to the parcels to which we currently have access; these are shown in the left side of the figure, which was derived from the map of ownership parcels maintained by Durham County (see Ownership Parcels). These parcels include publicly-owned lands, including those acquired as natural areas or parkland by Durham and Orange Counties. They also include the tracts of federally-owned lands within the Jordan Lake Project that are administered by the NC Wildlife Resources Commission as the New Hope Game Land. A few tracts of privately-owned lands are included where Durham County has acquired an easement for the New Hope Bottomlands Loop Trail.

Figure 1

Geology and Soils

Apart from an area of uplands included within the Hollow Rock Nature Park, the study area lies primarily within the Durham Triassic Basin, the remnant of a rift valley that formed approximately 220 million years ago when the ancient continent of Pangaea began to pull apart, the same event that formed the Atlantic Ocean. During that event, the block of land (a graben) now occupied by the Basin slipped downward between faults created by the stretching of the Earth’s crust, coming to rest at a sharply lower elevation than it formerly occupied. The sharp drop in elevation between the basin and the surrounding terrain created by this rift greatly increased the stream-cutting action of the primordial version of New Hope Creek and other streams flowing into the basin. As a result, the basin is now deeply buried due to the strong flow of sediments it has received – and continues to receive -- over the past hundreds of millions of years.

As a consequence of this sedimentation, the terrain within the basin is nearly level, with few exposed rocks, in strong contrast to the steep rocky canyons located just upstream (see Figure 2). The rock formations that it does possess are mainly sedimentary rocks formed secondarily from compression of the sediments flowing into the basin. Within the study area, the most obvious sedimentary formations are the large outcrops of sandstone located along the edge New Hope at the northwest corner of Hollow Rock Nature Park (the undercut rocks that give the area its name, however, are located north of Erwin Road).

Figure 2

In addition to the sedimentary formations, dikes and sills of igneous rocks formed around the periphery of the Basin where magma flowed into faults created by the rifting event. These intrusions typically have a mafic chemistry, having a higher pH than rocks typical of the Piedmont and are rich in minerals such as iron and magnesium. Several narrow intrusions of diabase – a mafic rock formation – intersect the New Hope gorge within the Korstian Division of Duke Forest and the upland portion of Hollow Rock Nature Park contains a mixture of diorite and gabbro, another type of mafic rock. One other, much larger source of mafic materials, is the wide expanse of gabbro, the Meadow Flats Pluton, located in the Blackwood Division of Duke Forest. Although located five miles from the study area, this pluton is nearly entirely drained by Mountain Creek, one of the headwater tributaries of the New Hope Creek watershed, and consequently may be the most important contributors of mafic sediments in the project area. For a detailed description of the geology of the headwaters area of New Hope Creek, see Bradley et al (2004).

Whatever their source, the sediments deposited in the Triassic Basin appear to have had a strong influence on the chemical and physical makeup of the soils within the study area. Roughly 70% of the soils within the project area belong to the Chewacla Soil Series (USDA-NRCS, Web Soil Survey; see Web Soil Survey). This is a typical bottomland soil of the Piedmont and is characteristically very deep, poorly drained, and frequently flooded. At the surface, pH ranges from very strongly acid to slightly acid to a depth of 40 inches. Judging from the number of basophilic plant species present in the study area, the soil pH in the study area is probably at the upper end of this range and most likely reflects the presence of the mafic rock formations located well upstream. A similar situation exists within the floodplain of the Roanoke River below the Fall-line. Although completely surrounded by the nutrient-poor, sandy soils typical of the Coastal Plain, the brownwater sediments carried down from the limestone-rich Ridge-and-Valley Province and other nutrient-rich areas of the Piedmont coat the floodplain and slopes of this valley with extremely rich sediments and support one of the largest concentrations of basophilic plant species in the state (see LeGrand and Hall, 2014).

Hydrological Features

The headwaters of New Hope Creek are located in west-central Orange County about 9.5 miles to the west of the Triassic Basin. Before flowing into the gorge section within the Korstian Division of Duke Forest, New Hope Creek is a typical, moderately-sized Piedmont stream, with a single, relatively straight channel, a rocky or gravelly streambed, and a narrow floodplain. Following its passage through the rocky gorge within the Korstian Division of Duke Forest– a drop in elevation of 151 ft in 2.7 miles -- New Hope Creek becomes drastically different in character.

Within the Triassic Basin, its floodplain widens to as much as a half mile in some areas and the flat terrain favors the development of meandering channels and old oxbows, features that are far more typical of the Coastal Plain than the Piedmont. From a rocky bottom, swift flow, and well-oxygenated waters, the creek itself develops a sandy or silty bottom, slow flows, and lower oxygen content. The channel formed by New Hope Creek as it flows through the flats of the Triassic Basin has fairly low banks, indicative of low stream-cutting action, which allows for frequent overbank flooding. Floodwaters are also distributed across the floodplain by old relict channels that are normally dry but that divert flow through an anastomosing network at high water levels. These old channels connect to a large number of depressions that temporarily fill with water during a flood, providing breeding sites for a number of amphibian species. Other depressions are big and deep enough to create more permanent oxbow ponds that support aquatic species, including Green Frogs, Mosquito Fish, and Pond Sliders, throughout the summer.

Beavers also create semi-permanent ponds, which they construct mainly on channels with perennial flows rather than the shallow, relict channels where the oxbows are found. Beaver ponds were major hydrological features in eastern North America prior to the early 1900s, when beavers were nearly extirpated from eastern North America. They were gone from North Carolina from the 1910s until they were restored in the in selected watersheds in 1940s and 1950s. Since that time, they have now re-occupied much of the state. Within the study area, Beavers are common along New Hope Creek where they mainly occupy bank dens and have not constructed dams. A series of beaver ponds has existed along Dry Creek for several decades, however (see Hall, 1995), and there is a recently constructed pond located in the Hollow Rock Nature Park.

Land Use History

Frequent and extensive flooding is responsible for many of the distinctive features of the study area. It is also largely responsible for the continued existence of the natural ecosystem itself in this long-settled and now rapidly developing area. The frequent flooding of the bottomland has long limited both agricultural uses and development of permanent structures within the floodplain and continues to do so. Even so, signs of past human uses of the area can be seen in aerial photos that were taken of Durham County in 1940 (Figure 3) and 1972 (Figure 4) (USDA Historical Aerial Photos, UNC-CH Library).

Figure 3

Figure 4

As shown in the 1940 photo, the northern, central, and southeastern portions of the Mt. Moriah Bottomlands were in cultivation or open pasture at that time. Smaller areas of similar land uses can also be seen within the New Hope Bottomlands and Mud Creek Bottomlands, and a very small clearing existed in what is now the Hollow Rock Nature Park. Many of these clearings were still present 1972 and continued to be in active use until the County acquired them as open space reserves between 1994 and 2003.

Some of the areas that were forested in 1940 have stayed in that condition for the subsequent 80 years. In the northern portion of the study area, these tracts include most of the Hollow Rock Nature Park and a couple of stands in the Mt. Moriah Bottomlands. By far the largest expanse of forest that has persisted within the study area is the tract that forms the core of the New Hope Bottomlands. Numerous trees exist within that area that are over 1.5 to 2.0 ft in dbh (diameter at breast height) and have canopies reaching 100 ft in height (Hall et al., 1999; LeGrand, 1999). Estimates of the age of this stand range from 100 to 150 years, which would put the last time when this tract was cleared close to the turn of the Twentieth Century, when a paroxysm of forest cutting swept across much of the eastern United States.

Even within the areas that are now completely covered with mature hardwoods, there are at least some traces of past human uses. Strands of old barbed wire deeply imbedded within trees indicate at least some past use as forest pasture for livestock. Some of the channels that exist within the floodplain – especially those that run a straight course away from the depressions – appear to represent attempts to drain the floodplain. In other places, depressions are surrounded by artificial berms probably to create watering sources for livestock.

Figures 5 and 6 shows the current condition of the study sites, based on aerial photos taken in 3/9/2021 (obtained from the Durham County GIS Services). The study sites are now almost completely forested, with most of the previously open areas having succeeded to stands of Loblolly Pines (which show up as dark green on the photos) and with even those now succeeding to hardwoods. Only a small clearing in the Hollow Rock Nature Park is still maintained as a meadow supporting native old field species. The powerline corridor (Figure 6) that runs through the center of the New Hope Bottomlands and the southern portion of the Mt. Moriah Bottomlands also supports old field species but is maintained as an open area through use of herbicides. The same is true for the road and sewer-line rights-of-way located on the outer edges of the study sites.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Most of the study area is roadless, with only US 15-501 and Pickett Road crossing areas within the overall project area itself. Bridges over New Hope Creek at Old Chapel Hill Road, US 15-501, and Erwin Road allow at least some passage of wildlife both through the study area and to the adjoining natural areas up and downstream. The bridge crossing at US 15-501 was, in fact, designed specifically to facilitate wildlife movements (see Kleist et al., 2007). Within the individual study sites, no hiking or biking trails currently exist within the Mt. Moriah Bottomlands, where access points are, in fact, very limited. Hollow Rock Nature Park has a network of trails and is a popular hiking area. The Loop Trail that runs through the New Hope Bottomlands receives more limited visitation, largely due to its frequently muddy or flooded conditions.

Biodiversity

Biological inventories conducted previously within the project area showed it to possess one of the richest floodplain ecosystems in the eastern Piedmont (see References for the citations for these surveys). A total of 1,376 of the records compiled in our database come from these earlier surveys, which documented the presence of 472 species. Most of these records are for vascular plants, vertebrates, and a few species of invertebrates, primarily butterflies and dragonflies. Based on the richness of the taxa already documented, we expect to find an equally rich assemblage of species in the groups we are adding in the current survey.

Among the most noteworthy species documented in these surveys was a population of Shellbark Hickory discovered by Harry LeGrand (1999). The population in the New Hope Bottomlands is one of only two currently known to exist in North Carolina, and one of only a handful that occur east of the Appalachians. Even rarer, White and Pyne (2021) recently discovered a population of White Nymph (Trepocarpus aethusae), an Umbel not previously recorded north of South Carolina and again that has only a few populations east of the mountains. Other rare plants include Dwarf Ginseng, Atlantic Isopyrum, and Seneca Snakeroot, all of which were recorded just outside the current study area, within the same ecosystem that extends well south of Old Chapel Hill Road (Hall et al., 1999). The rarest animal recorded in the New Hope Bottomlands, the Four-toed Salamander, was also recorded in that area.

The rare plant species are strongly associated with the rich, moist soils found in the bottomlands along New Hope Creek or on the adjoining slopes. The Natural Heritage Classification of Natural Communities of North Carolina (Schafale and Weakley, 1990; Schafale, 2012) places this association in the Piedmont Bottomland Forest (Typic Low Subtype). Other natural communities found within the study area include Piedmont Levee Forest, Piedmont Swamp Forest, and Floodplain Pools. Remnants also exists of Mesic Mixed Hardwoods (Piedmont Subtype) along some of the few slopes that have so far escaped development. Upland communities found in the Hollow Rock Nature Park include Dry-Mesic Oak-Hickory Forest and Dry Oak-Hickory Forest. Based on the mature, high quality condition of these natural communities, along with the presence of the rare plant species, the Natural Heritage Program ranks the New Hope Bottomland Forest (including the area south of Old Chapel Hill Road) as an Exceptional Natural Area. The Dry Creek/Mt. Moriah Bottomlands, which are more strongly disturbed and lack the documented species of rare plants and animals, is rated as only Moderate in significance.

In this project, we define habitats somewhat differently than the way the NHP Natural Communities are described. As in the NHP classification, we follow the usual practice of defining habitats based on sets of abiotic and/or biotic factors, along with particular ranges of values for certain factors, e.g., temperature or moisture conditions. In order to qualify as a habitat, however, we also require that there be a set of species that show high fidelity to those factors; there must be a characteristic set of inhabitants in order for a set of environmental factors to constitute a habitat. In our system, these determining species for a given habitat are those that have at least 80% of their occurrences at sites that have that specific set factors and value ranges. Although each species has a unique set of factors to which it is adapted, we use a sufficiently general set -- much the same as used in NHP community classification -- such that habitats are typically associated with multiple species. This definition of habitats is similar to how it is done for individual species, one consequence of which is that our multi-species habitats can overlap extensively with one another at any one site. For example, habitat for Blue Jays completely overlap with that of the Four-toed Salamanders, indicating that they have certain habitat factors in common. However, Blue Jays occur far more broadly, reflecting the much broader range of environmental tolerances and resources that determine their limits. This overlap between habitats is a major difference from the community approach, where only one community exists on a particular area of ground. The overlapping nature of our habitats is illustrated in the examples given below for our particular study area.

The most distinctive habitat features of the New Hope Creek floodplain are its frequent, but short-duration flooding; its nutrient-rich, wet alluvial soils; and its large expanses of mature, closed-canopy hardwood forests. Within the Piedmont of North Carolina, twelve species of plants are highly associated with this particular combination of factors (and range of values), including Shellbark Hickory, Box-elder, American Sycamore, Virginia Virgin's-bower, and several species of graminoids, vines, and forbs. Additionally, eleven species of moths are highly associated with these plants. Consequently, these insects show the same degree of fidelity to the factors as shown by the plants and are therefore treated as equally characteristic species of this habitat. The same would be true for any species of mycorrhizal fungi that show a high level of association with the plant members of that habitat, or any other taxonomic group that have species that show high fidelity either with the abiotic factors directly or the other species that are characteristic species of this habitat. Note that our method of defining habitats gives equal weight to all of these species, whereas the standard community approach gives the greatest weight to the dominant species found with a given unit, based on the primacy of their ecological role, their abundance, or other prominent aspect (the moths would be rarely, if ever, given such weight).

We use the term Rich, Wet Hardwood Forests to refer to this collection of habitat factors and characteristic species. Within the study area, several other habitats overlap this habitat. For example, the Rich, Wet-Mesic and Rich Dry-Wet Hardwood Forests require nutrient rich soils and can occur in floodplains. However, as implied by the different moisture characteristics in their names, they are not limited to floodplains and can occur up on slopes or even drier ridges. The Rich, Wet-mesic Hardwood Forests have 126 characteristic species, including 86 plants, 39 insects, and one bird. The Rich Dry-wet Hardwood Forests have 28 characteristic species, consisting of five plants and 23 insects. Although these three habitats differ in their degree of association with floodplains themselves, we expect all of the 176 species belonging to these three habitats to be potentially present in the floodplain of New Hope Creek.

Still other habitats are defined by frequent flooding and the presence of a mature, closed canopy hardwood forest, but are less specific in their association with rich substrates. These include the General Wet Hardwood Forests (18 characteristic species), which are associated with bottomlands that are flooded for only short durations, and the General Wet-Hydric Floodplains (36 species), which includes permanently flooded swamps and ponds as well as bottomlands that are flooded for only shorter periods. Even more general are habitats associated with closed canopy forests, whether or not they are located in floodplains or uplands. Within the study area, these include the General Oak-Hickory Forests (144 species) and the General Hardwood Forests (102 species). Floodplains also include a number of wetland habitats that do not require the presence of a closed canopy forest. These include General Broadleaf Herbaceous Mires (40 species) and General Sedge, Grass, and Rush Mires (63 species). Isolated pools have their own set of distinctive species (4) as do General Beaver Ponds and Semi-natural Impoundments (23 species). Habitats associated with Piedmont streams include General Waters and Shorelines (18 species), General River Bars and Sparsely Vegetated Shorelines (13 species), and Shoreline Shrublands (55 species).

Altogether, we have currently identified 70 habitats within the New Hope Creek floodplain. These are listed, along with their species that have been documented within the study area, in the Habitats table that can be accessed using the menu shown on the Home Page of this website. This is a much greater number than the natural communities that have been described for the study area. That reflects the greater use of biotic factors – e.g., symbiotic associations between species – in our approach, as well as the greater range of taxonomic groups that we consider. A main practical advantage is that our approach can be used to predict the species that should occur within our study site. For example, we expect all 23 species that are characteristic of Rich, Wet Hardwoods to occur within the study area. A comparison between the species we actually observe to this expected number provides a way of gauging habitat integrity, although factors such as the detectability of the species needs to be taken into account. Such comparisons can be done on a habitat-by-habitat basis but we can also conduct this analysis at the level of the entire study area, combining the expectations for all habitats. We can also do this on a taxonomic basis, for example moths or vascular plants, or on groupings representing ecological functions, such as herbivores or detritivores. These comparisons will form the basis for our overall assessment of the project area as a whole, or its individual subunits.

As in our taxonomic websites, the purpose of this website is to share the information we gather as widely as possible. The data collected for the New Hope Survey area not only provides the Durham County Open Space Program with the information they need to make management and land use decisions, but also keeps the public informed about the state of the biodiversity of this key conservation area. In order for conservation to be effective, a solid scientific case needs to be made that a particular area merits a high degree of attention based on the presence of imperiled species, or the overall quality of its habitats and ecosystems. Just as critically, conservation needs the support from a well-informed and interested public. This project is aimed at achieving both of these goals.

Although the survey has now been completed, we will continue to maintain this website and plan to update the observations made in the project area on at least an occasional basis. These will include both the records obtained directly by members of the NCBP and those submitted to our taxonomic websites by the members of the public. Selected records will also be added from iNaturalist and other online sources.

New Hope Creek Biodiversity.pdf

Appendix 1. Summary of Myxomycete Observations

Appendix 2. Summary of Fungi Observations

Appendix 3. Summary of Lichen Observations

Appendix 4. Summary of Bryophyte Observations

Appendix 5. Summary of Vascular Plant Observations

Appendix 6. Summary of Arachnid Observations

Appendix 7. Summary of Odonate Observations

Appendix 8. Summary of Orthopteran Observations

Appendix 9. Summary of Hemipteran Hopper Observations

Appendix 10. Summary of Butterfly Observations

Appendix 11. Summary of Macro-Moth Observations

Appendix 12. Summary of Micro-Moth Observations

Appendix 13. Summary of Bee Observations

Appendix 14. Summary of Vertebrate Observations

Appendix 15. Summary of Other Animal Taxa Observations