Taxonomy

Class: AmphibiaOrder: CaudataFamily: PlethodontidaeSubfamily: PlethodontinaeAuthor: (Pope, 1928)

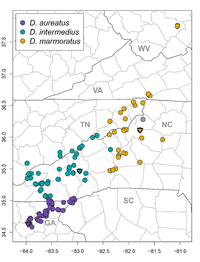

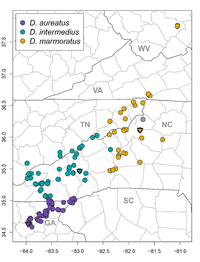

Taxonomic Comments: Members of the genus Desmognathus are commonly known as dusky salamanders because of their overall dark brown or dusky ground color. Like many plethodontid salamanders, they have proven to be a taxonomically challenging group that contains several species complexes. Kozak et al. (2005) documented 35 major lineages in the eastern US, even though only 22 species were formally recognized by taxonomists in 2021. This suggests that there are numerous cryptic species that remain to be described. A more recent comprehensive molecular survey of populations in the eastern US by Beamer and Lamb (2020) indicate that at least 45 major lineages or clades are present. D. marmaratus ) as a species that closely resembles the Black-bellied Salamander (D. quadramaculatus ) in being a relatively large Desmognathus with a stocky build, keeled and laterally compressed tail, cornified toe-tips and two rows of light spots that are usually present along each side of the body. If differs from the Black-bellied Salamander in having internal nares that form slits rather than round pores, in the coloration and patterning on the venter of adults, and in the profile of the head. Recent molecular studies by Beamer and Lamb (2020), as well as several previous studies, have shown that these two species are not monophyletic. Instead, populations of both species are interspersed within a strongly supported clade that contains all populations of D. quadramaculatus , D. marmoratus , and a third species, D. folkertsi . This major clade contains two subclades, including one that includes all D. quadramaculatus populations sampled south of the Pigeon River, as well as all D. marmoratus populations sampled in the Apalachicola and Savannah River drainages. The second subclade includes all populations of D. quadramaculatus sampled from east of the Tuckasegee River drainage basin (with one exception) as well as all populations of D. marmoratus sampled outside the Apalachicola and Savannah River drainages. In some cases populations of D. quadramaculatus are more similar genetically to D. marmoratus than to other D. quadramaculatus populations. Collectively, the research by Beamer and Lamb (2020) and others indicates the presence of a species complex that involves all three currently recognized species. After conducting additional molecular and morphometric studies, Pyron and Beamer (2022) recognized five species within the Black-bellied Salamander complex. These include a previously recognized species D. folkertsi , and four new species (D. amphileucus , D. gvnigeusgwotli , D. kanawha and D. mavrokoilius ) that replace what was traditionally known as D. quadramaculatus and certain populations of D. marmoratus . D. aureatus , D. melanius , and D. marmoratus ) based on Jones et al.'s (2006) and others work, but their taxonomic changes were not widely adopted by North American herpetologists. In the most recent work, Pyron and Beamer (2023) provide a comprehensive review of the literature, correct a nomenclatural error by Dubois and Raffaëlli (2012), and provide a systematic revision of three species of shovel-nosed salamanders that are currently recognized. All three occur in North Carolina and include, 1) D. aureatus (Martof, 1956) that occurs in northeastern Georgia, northwestern South Carolina, and small portions of the nearby border regions of North Carolina, 2) D. intermedius (Pope, 1928) that occurs in the Blue Ridge of western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, and appears to be restricted to the Tennessee drainages of major rivers in the central and southern Blue Ridge of North Carolina, and 3) D. marmoratus (Moore, 1899) from northeast of the Pigeon River in North Carolina to northeastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia. These three species do not represent a natural group as previously thought, but instead exhibit convergent phenotypes across multiple species, potentially driven by ancient episodes of adaptive introgression between ancestral lineages. Although there are some morphometric differences between species that are best determined using museum specimens, the three species are best identified by using their geographic ranges and the site where a specimen was observed. Species Comments:

Identification

Description: This is the largest of our shovel-nosed salamanders, with the SVL of adults ranging from around 28 – 85 mm (Pyron and Beamer, 2023). The dorsal ground color of the adults is typically dark brown but is often obscured by pairs of yellowish-brown spots that are diffuse and often fused to produce an overall indistinct dull yellowish-brown dorsal pattern. Some specimens may be completely devoid of patterning, so expect variation among populations. The venter is light colored in subadults, but becomes dark brown or dark gray in the adults and is often lighter in the center. The head is flattened, and the internal nares form slits rather than round pores as seen in other Desmognathus species. The toe tips are cornified and blackish. The males are larger on average, have enlarged maxillary teeth, papillate cloacae (smooth in females), and an inconspicuous mental gland (Martof 1962, Petranka 1998). A sample of the 20 largest males in a population in Haywood County varied from 61-73 mm SVL (mean = 65 mm) versus 52-65 mm (mean = 58 mm) for the 20 largest females (Martof 1962). In this species, vomerine teeth are present in all females and all but the largest males, which helps to distinguish this species from D. aureatus in areas of close contact. As with our other shovel-nosed salamanders, the site of collection is most useful in identifying species since none of the species occur sympatrically (see distribution map above). Online Photos: Google iNaturalist Observation Methods: The juveniles and adults are most common in riffle areas of streams and are perhaps best collected by kick-netting.AmphibiaWeb Account

Distribution in North Carolina

Distribution Comments: This is yet another southern Appalachian endemic that is found in the southern half of the Blue Ridge in North Carolina, and in adjoining areas in extreme eastern Tennessee. This species has been documented in extreme western Yancey Co., northern Madison Co., Haywood Co., northern Transylvania Co., northern Jackson Co., Swain Co., Graham Co., Macon Co. and eastern Clay Co. It has been confirmed in the drainages of the Lower Little Tennessee River, the Upper Little Tennessee River, the Tuckasegee River, the lower French Broad River, the Pigeon River, and the upper French Broad River (Pyron and Beamer, 2023). Desmognathus intermedius is parapatric with D. aureatus near the Georgia-North Carolina border in eastern Clay Co. and southwestern Macon Co., but the two species are in different drainage basins and have little opportunity to contact one another (Jackson 2005).Distribution Reference: Pyron and Beamer (2023)County Map: Clicking on a county returns the records for the species in that county.

GBIF Global Distribution

Key Habitat Requirements

Habitat: The Western Shovel-nosed Salamander is an almost entirely aquatic species that prefers cool, well oxygenated streams at elevations of approximately 300–1500 m (985-4,921'; Pyron and Beamer, 2023). This species is generally more common in second and third-order streams in the southern Appalachians. Adults reach their highest densities in small to medium-sized streams with broken rocks and loose gravel, but local populations can also be found in headwater streams with gentle gradients (Martof 1962, Petranka 1998). Shallow rifle areas in streams that have angular rocks, loose gravel and moderate to fast flowing water provide ideal microhabitats for the juveniles and adults.Biotic Relationships: This species co-occurs with a variety of potential predators and competitors, but biotic interactions with these are largely undocumented.

Life History and Autecology

Breeding and Courtship: The courtship behavior is undocumented.Reproductive Mode: Most aspects of the life history of this species are undocumented. Martof's (1962) comprehensive work on the natural history of shovel-nosed salamanders was mostly based on studies of D. aureatus , and our knowledge of the life history of both D. intermedius and D. marmoratus is very limited. Aquatic Life History: The diet of the subadults and adults is primarily composed on insects. Martof and Scott (1957) found that mayflies and caddisflies were the most important prey in a Haywood County population. Other prey included dipterans, stoneflies, beetles, hymenopterans, homopterans, crayfishes and snails.

General Ecology

Adverse Environmental Impacts

Interactions with Humans: The introduction of non-native trout into streams in western North Carolina has undoubtedly resulted in many losses of the larvae and adults due to predation (Martof, 1962).

Status in North Carolina

NHP State Rank: [S4]Global Rank: GNREnvironmental Threats: This species requires cool, highly oxygenated streams with minimal sedimentation. Timbering and developments that increase sedimentation in streams and destroy microhabitats that are used for nesting and cover constitute the greatest threats to local populations. Status Comments: This is a southern Appalachian endemic that is found in the southern half of the Blue Ridge in North Carolina, and in adjoining areas in extreme eastern Tennessee. It has been documented in extreme western Yancey Co., northern Madison Co., Haywood Co., northern Transylvania Co., northern Jackson Co., Swain Co., Graham Co., Macon Co. and eastern Clay Co. It is a highly aquatic species that rarely leaves the water and can reach high local densities in the riffle sections of streams. Most populations are in national parks or national forests and have a relatively high degree of protection from timbering or development that could impair streams. The greatest future threats are likely those associated with climate change and the excessive deposition of atmospheric pollutants. Stewardship: This and other stream-breeding salamanders in the Blue Ridge prefer high-quality streams with minimal siltation. Having wide buffers of mature or old-growth hardwoods along stream will help to protect this and many other salamanders in the southern Appalachians.

»

»

»

»