|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

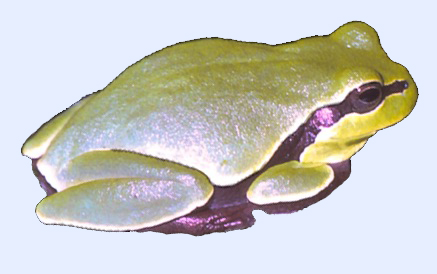

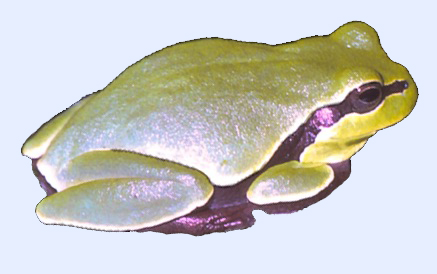

Photo Gallery for Plethodon metcalfi - Southern Gray-cheeked Salamander

| 9 photos are shown. |

| Recorded by: B. Bockhahn

Macon Co. |  | Recorded by: B. Bockhahn, J. Thomson

Macon Co. |

| Recorded by: B. Bockhahn

Macon Co. |  | Recorded by: B. Bockhahn, J. Thomson

Macon Co. |

| Recorded by: B. Bockhahn

Macon Co. |  | Recorded by: B. Bockhahn

Macon Co. |

| Recorded by: M. Krintz

Transylvania Co. |  | Recorded by: Owen McConnell

Graham Co. |

| Recorded by: Owen McConnell & Roger Rittmaster

Graham Co. |

»

»

»

»