|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

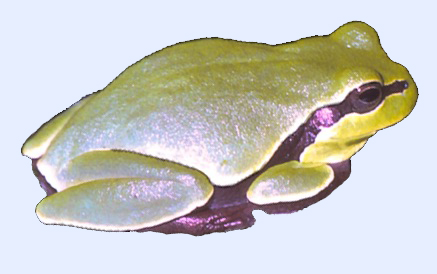

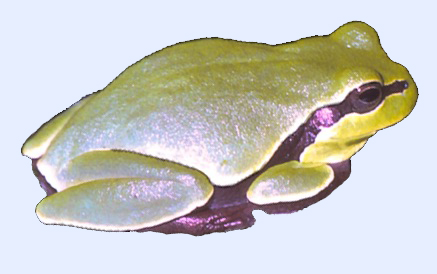

Photo Gallery for Plethodon richmondi - Southern Ravine Salamander

| 8 photos are shown. |

| Recorded by: A. Burgos-Melendez, R. Passino, E. jonas, R. Elliott, M. Ortiz

Ashe Co. |  | Recorded by: S. Becker, C. Ferrell

Watauga Co. |

| Recorded by: S. Becker, C. Ferrell

Watauga Co. |  | Recorded by: Stephen G Dowlan

Watauga Co.

Comment: iNaturalist: Creative Commons; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ |

| Recorded by: Steve Hall and Bo Sullivan

Ashe Co. |  | Recorded by: E. Corey

Ashe Co. |

| Recorded by: E. Corey

Ashe Co. |  | Recorded by: E. Corey, Davidson College personnel

Ashe Co. |

|

»

»

»

»