Welcome to the "Reptiles of North Carolina" website! |

Rhadinaea flavilata by Sam Bluestein Pine Woods Littersnake |  Chrysemys picta by Steve Hall Painted Turtle | Opheodrys aestivus by Erich Hofmann Northern Rough Greensnake |  Chelonia mydas by Newman Green Sea Turtle |

Aims of this website Our aim with this project is to provide an easily available source of information about the turtles, lizards, snakes, and crocodilians that occur in North Carolina.

Working in partnership with scientists, naturalists, conservationists, and the general public we also use this website to track changes in the abundance, distribution, and status of these species

across the state.

The species accounts are continually being updated for all reptile taxa. Those included in this website have several key parts: 1) a description the features of the species, including the key characteristics that distinguish it from similar species. A photo gallery is included to illustrate these features and to show the range of their variation2) a county atlas showing the distribution of each species of reptile in North Carolina, based on vetted records 3) a description of the life history of the species, particularly as it exists in North Carolina 4) a description of the habitat and ecological associations of the species, again with special reference to how they exist in North Carolina 5) an assessment of the conservation status of each species, describing their specific risk factors and estimating the probability of the species becoming extirpated from the state

|

|

Stats Number of NC taxa: num_nc_species Number of species: 75 = 70 native and 5 established non-native Number of records: 18,156 |

WHAT IS A REPTILE?

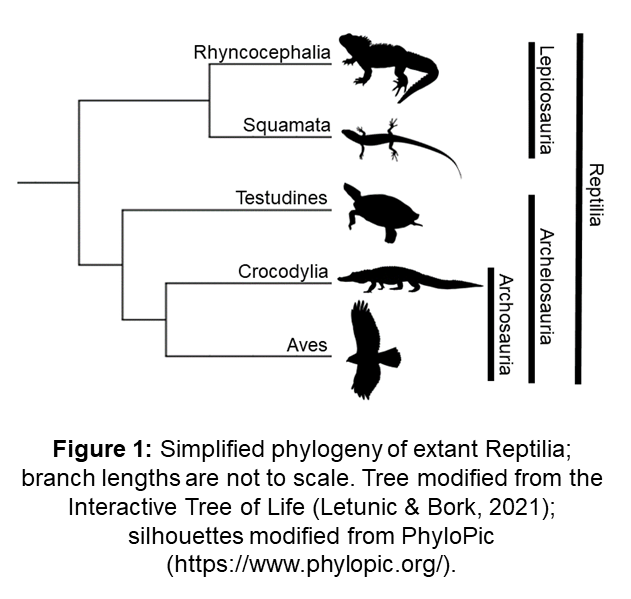

WHAT IS A REPTILE?The common definition of reptile is one most people are familiar with – ectothermic (“cold-blooded”) scaled tetrapods that lay eggs, including lizards, snakes, turtles, and crocodilians. While this definition holds some truth, it is also incomplete, belying both the species diversity and physiological diversity of the group, as well as long-standing taxonomic issues related to what is (and what is not) a “reptile”. The advent of modern molecular techniques for assessing evolutionary relationships has fundamentally changed our view of the definition of “reptiles”; we now know that older classifications based primarily on morphology render the group paraphyletic—that is, the class Reptilia includes only some, not all, of the groups descended from a common ancestor. Taxonomy & Evolutionary History Reptiles arose approximately 315 million years ago from a common ancestor with synapsids, which gave rise to modern mammals. The class Reptilia, as currently considered, is comprised of two major extant groups often labeled as subclasses or superorders: Lepidosauria and Archelosauria (Figure 1). Extant lepidosaurs comprise two orders: Rhynchocephalia—whose only extant member, the tuatara, is endemic to New Zealand; and Squamata—consisting of thousands of species of lizards, worm lizards (amphisbaenians), and snakes. Extant Archelosauria also consists of two orders: Testudines—turtles, whose exact taxonomic placement within Reptilia has long been problematic and the subject of much research and debate; and Archosauria—consisting of Crocodylia (crocodilians) and Aves (birds). It is this last category, the archosaurs, that renders the class Reptilia paraphyletic, as birds are traditionally assigned to their own class despite being nested phylogenetically within reptiles. The centuries of separation between these groups in both the public eye and academically means that although the traditional definition of a paraphyletic Reptilia violates taxonomic rules, it still makes the most sense to most people. However, it is important to note that birds are, in fact, a unique set of reptiles. On the Reptiles of North Carolina page, we will stick to the traditional view of Reptilia, which for our purposes include all “non-avian” reptiles; thus, any reference to “reptiles” here is exclusive of birds. In North Carolina, we need only focus on lizards, snakes, alligators, and turtles.  The American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) is our only extant non-avian archosaur, and a member of the family Alligatoridae within the order Crocodylia. Only two species of Alligator are extant, the other being the smaller Chinese Alligator (A. sinensis).

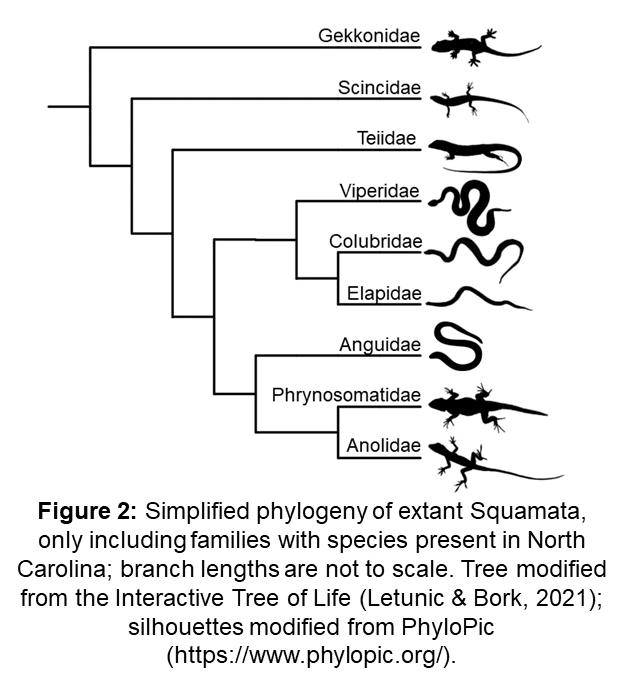

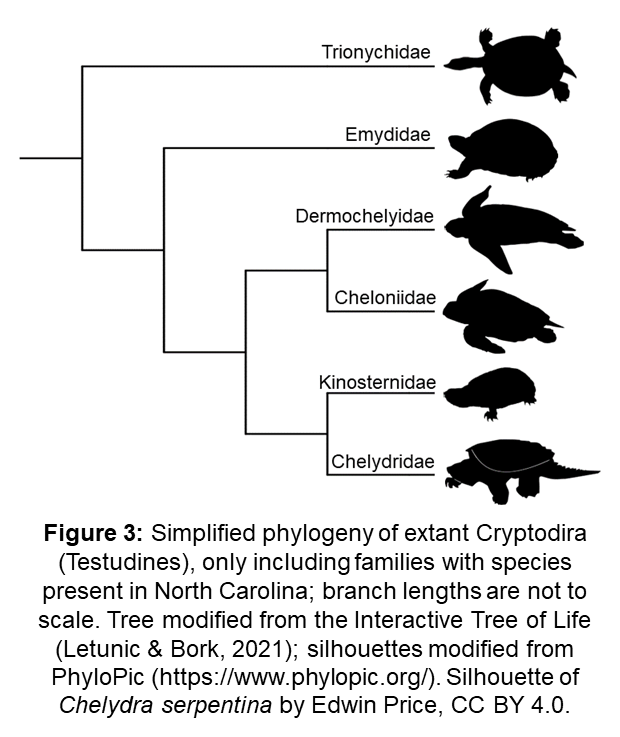

The American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) is our only extant non-avian archosaur, and a member of the family Alligatoridae within the order Crocodylia. Only two species of Alligator are extant, the other being the smaller Chinese Alligator (A. sinensis).Within Squamata (Figure 2) are the lizards and snakes, as well as an obscure group of primarily tropical, mostly legless squamates absent from the majority of the United States except Florida, called amphisbaenians (“worm lizards”). “Lizards” (sometimes placed in a suborder “Sauria”) is also a paraphyletic term; all snakes (Serpentes) are nested within all other squamates, including our local species of skinks (Scincidae), glass lizards (Anguidae), anoles (Anolidae, previously Dactyloidae), racerunner (Teiidae), and fence lizard (Phrynosomatidae), as well as introduced species such as geckos (Gekkota, most in Gekkonidae). Thus, snakes are actually more closely related to glass lizards, anoles, and fence lizards than skinks or geckos are! Similar to our use of the term "reptile", our usage of the term "lizard" on this site will refer to lizards exclusive of snakes. Extant North Carolina snakes traditionally are classified into three families: Colubridae (all nonvenomous snakes in the subfamilies Colubrinae, Dipsadinae, and Natricinae), Viperidae (pitvipers such as rattlesnakes, cottonmouths/water moccasins, and copperheads, all of whom are in the subfamily Crotalinae), and Elapidae (coral snakes). However, many recent works consider the subfamilies of Colubridae to be families themselves, restricting Colubridae to species within the subfamily Colubrinae, and elevating the other two subfamilies to full families - Dipsadidae and Natricidae. Testudines as a group have been the subject of much taxonomic debate, with some studies placing them as stem reptiles, some as more closely related to lepidosaurs, and others more closely related to archosaurs. Most traditional morphology-based phylogenies placed Testudines as basal to both archosaurs and lepidosaurs. However, modern molecular studies have resolved this confusion (somewhat), and currently Testudines is considered the sister group to archosaurs, more closely related to crocodilians than squamates within Reptilia (Figure 1). All North Carolina turtles are in the suborder Cryptodira (“hidden-necked turtles”; Figure 3). Soft-shelled turtles (Trionychidae) are sister to the hard-shelled turtles, which include the vast majority of our species: sea turtles (Chelidoidea: Cheloniidae and Dermochelyidae), snapping turtles (Chelydridae), mud and musk turtles (Kinosternidae), and terrapins/pond turtles (Emydidae).  Although it does not reach the levels of diversity found in states like Texas or Florida, North Carolina is home to nearly 40 species of snakes, 11 lizards, 24 turtles, and one alligator, with much of that diversity located in the Coastal Plain; recent introductions of several non-native turtles and lizards push the total number of reptile species in North Carolina to approximately 75. Additionally, several unique populations of reptiles in North Carolina—currently referred to various subspecies or clades—may represent distinct species and are in need of further investigation. As taxonomic research—especially using modern genomic techniques—continues, these values may fluctuate as we gain a better understanding of species boundaries and evolutionary relationships. Physiology The diversity of body plans, physiologies, and ecological niche use within Reptilia are evident when looking across their phylogeny. While most reptiles reproduce sexually, some can reproduce asexually, leading to parthenogenesis (“virgin birth”). Most reptiles lay eggs, but some species have evolved ovoviviparity—where eggs are carried and hatch within the mother, leading to “live” birth—or even placental viviparity—where embryos are sustained by placental organs (primarily through gas exchange) as they develop inside the mother. Ovoviviparity is common in pitvipers, and placental viviparity is known in some fence lizards and natricine snakes. Additionally, some species, most notably sea turtles and alligators, exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination, where the temperature of the egg during will determine the sex of the developing offspring. Unlike amphibians, reptiles do not have a biphasic life cycle, but some do exhibit ontogenetic changes in color, pattern, venom production and composition, and/or diet preferences. Additionally, some species, such as the broadhead skink, will undergo morphological changes during breeding times. Most reptiles are ectothermic, requiring environmental heat to maintain internal body temperature, but some—including the leatherback sea turtle—are mesothermic, an intermediate adaptation that allows for elevated body temperatures through metabolic heat production. These adaptations allow reptiles to have low resting metabolisms that require substantially less food than a comparably sized mammal would need to sustain body function. Very few reptiles vocalize, in contrast to birds or frogs. Snakes “hiss” by forcing air through their glottis. Non-native Hemidactylus geckos can produce distinct vocalizations, including territorial/agonistic chirps and distress calls. Alligators produce a wide range of bellows, hisses, growls, and “chumpfs” by sucking in and blowing out air from their lungs. Juvenile alligators also produce a high-pitched whine as they are beginning to hatch. Many turtle species also produce various clicks, whistles, grunts, and snorts. Venoms are among the most fascinating—and to some, frightening—aspects of reptile physiology, as six of our native species produce venoms that are medically significant to humans. Snake venoms are not single entities, but complex mixtures of proteins and enzymes that interact in different ways with their target. Importantly, these mixtures vary between species, and can even vary between and within populations of the same species, as recent research is uncovering. Five of North Carolina’s extant venomous snakes are pitvipers in the subfamily Crotalinae; these species (rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths/moccasins) possess hemotoxic venoms that interact with blood, leading to clotting issues, and tissue, causing necrosis. Our local coral snake is in the family Elapidae, more closely related to cobras and kraits; it possesses a neurotoxic venom which targets the nervous system of prey in order to cause paralysis or breathing difficulties. Although numbers vary due to reporting (or lack thereof), on average fewer than 100 people are bitten in North Carolina each year by venomous snakes, and since 2000 only two fatalities due to native snakes have been recorded. Some colubrid species previously considered “non-venomous” have been found to possess weak venoms used only in prey capture and are not considered dangerous to humans; these species are often referred to in primary literature as “mildly venomous” or “not medically-significantly venomous” and include inoffensive species such as the Southeastern Crowned Snake, Eastern Hog-nosed Snake, and Common Gartersnake. The vast majority of snakes in North Carolina are not medically-significantly venomous and are harmless to humans and pets. |

|

The Reptiles of North Carolina Website is being developed through a partnership between the North Carolina State Parks System (NC DPR) and the North Carolina Biodiversity Project (NCBP), a non-profit, education- and conservation-oriented association composed of field biologists specializing in taxonomy, ecology, and conservation of the state’s native species and ecosystems. This partnership serves NC DPR’s mission of providing "environmental education opportunities that promote stewardship of the state's natural heritage". It is also serves NCBP core interests in promoting awareness and interest in the general public concerning the state’s rich variety of native species, and in generating a wide base of support for the conservation of these resources.

|

|

How to Get Involved The mission of the NCBP is to gather information on the biodiversity of North Carolina and to then disseminate it as widely as possible. As a key part of that process, we want to involve the public as much as possible, not only as recipients of this information, but as active partners in its acquisition. For that reason, we have created an online submission form that can be used by anyone -- expert or novice -- to send records to this website. We also need to ensure that the data we accept and subsequently publish on this website is as scientifically accurate as we can make it. The following description provides information on the types of data we are looking for and the steps we follow in processing records that are submitted to us. Submitting a RecordBefore submitting a record, read Terms of Use/Privacy Statement. Our intention is to make the information gathered in the website as widely available as we can make it. We therefore follow the guidelines established for Fair Use of published materials. However, for anyone who would like to have stronger copyright recognition for the photographs they submit, we accept photographs that contain the copyright symbol, indicating the need for the photographer to be contacted for any third party use. To send us a record, click on Submit a Public Record on the menu located on the left side of the Home Page. Only records of reliably identified species serve our interests to document the distribution, natural history, and conservation status of the reptiles of North Carolina. To make the record most useful for these purposes, therefore, we require that certain information be filled in, as indicated in red text on the form. Species Name The submitters themselves need to take the initial step in trying to identify the species the record represents; a provisional scientific or common name must be entered in order to open the main submission form. This requirement helps the submitter learn more about the identification process (and its problems). It also helps us process the records more quickly. For help in establishing this preliminary identification, click on the Identification Guide located on the menu at the top of the Home Page. There are several web sites that will help with the identification. Although your initial identification does not have to be completely accurate – we will vet the photograph or other evidence as part of the acceptance process – the more precise it is, the faster we can process the submission. Conversely, records that require more time and effort on the part of our reviewers are likely to be delayed in acceptance, sometimes (we regret to say) indefinitely. If you are unable to identify your individual—especially in the case of a possible introduced species—you may use the "Unidentified Turtle/Lizard/Snake" buttons instead; however, it is greatly preferred that submissions include a more precise identification when possible. Identity of the Observer The name of the person must be included and an email address where the submitter can be reached; we do not accept any records from anonymous or otherwise unverifiable sources. Only the observer’s name will show up in the species accounts, not the email address, which will be used only to notify the submitter concerning the status of their record (see Vetting Process below); it will not be shared with anyone outside of the website group without permission from the submitter. Date and Location of the Record For the record to be useful to us, we require information on the date and location of the observation. The dates will be used to compile phenology charts, with separate charts used for reproductive activity and general above-ground activity by the adults. Locations for all records – adults or juveniles – will be used to fill in the distribution maps displayed for the species. Although only the counties will show up in the public display on the website, we need more accurate locational information to help identify sites of particular conservation interest, as well as to help identity the habitat and landscape context where the record was made. In some cases the location where the observation was made can be important in the identification of the species. The coordinates of the location – in decimal degrees -- can be entered using either data from a personal GPS or using Map It, the mapping tool included on the form. We would also like the name of the site to be included, if identifiable (e.g., a town or nature preserve), along with any descriptive subsite information that can be provided (e.g., neighborhood name, street address or location along a road, or topographic location – e.g., floodplain or ridgetop). Number of Individuals; Methods of Observation; Life Stages The abundance of a species is usually one of the main factors determining its conservation status – the less abundant the species, the higher its presumed risk and hence the higher its priority for protection. However, the number of reptiles seen at a particular time and place varies widely, depending on weather conditions, timing of the life cycle of the particular species, and the methods used to make the observations. While not required -- we will enter a single individual as a default if no estimates of numbers are recorded -- either exact counts of the individuals seen at a given time or estimates (for observations above 5 individuals) provide useful information on population sizes and trends. Habitat Gathering information on the habitats used by the species is one of the most important goals of this project -- we use this information to help determine the ecological and conservation needs of the species. One of our main missions of the NCBP overall is to acquaint the public about the diversity of habitats we have in North Carolina and how each one plays a role in sustaining our native biodiversity. The habitats listed on the entry form are fairly simplified, our hope being that most people will be able to use them to describe the general environment where the record was obtained. A description of each habitat type is also provided that can be pulled up by clicking on the name of the habitat. Note that more than one habitat type can be selected. Since some reptiles will move great distances in pursuit of prey or a reproductive partner, we ask that all habitat types within a radius of 100 yards be recorded.

Comments The Comments section is optional but can be used to record information about habitat, mating behavior, predator-prey interactions, or other behavioral or ecological observations of interest. Inclusion of this information makes a record far more valuable than just a dot on the map or bar on the phenology chart (as valuable as those pieces of information are). Predator-prey interactions are of particular interest. Adding a Photograph Photographs provide the basis for documenting a record and must be included as part of all submissions (records from specimens obtained from surveys conducted by expert herpetologists are recorded through a separate process). For photographs stored on your computer, use your file browser to locate the file; open the file by clicking on the name or image, and then click on the Open button shown at the bottom of the form. Usually only one photograph should be entered per species per site per date, but up to three shots can be entered, showing a given individual from different angles or several individuals displaying a range of variation in pattern or other features. Add additional information in the comment box that will help confirm the identity of the species (e.g., "keeled carpace; pair of pale stripes on the sides of the head") Completion of the Form Following the Security Check and acceptance of the Terms of Use at the bottom of the form, click on the Submit button to enter the completed record. Vetting ProcessOnce a record has been submitted, the proposed identification is reviewed by our team of experts to confirm its accuracy. Accepted records will be displayed for a short time on the Recent Entries table and will be entered at the same time to the appropriate Species Account. Note that in some cases, we may not be able to identify the specimen to species and may decide to place them in accounts we have set up for unidentified species belonging to a given genus. Where the record is not accepted or where we have identified it as a a different species, or where additional information is required, a message may be sent to the submitter via email. Currently, we are able to process the records within a two week period (usually less). |

How to Identify a ReptileThe identifying features of each of the snakes, lizards, turtles, and crocodilians that occur in North Carolina are described in the species accounts. These descriptions emphasize the features that we ourselves use in vetting records that are submitted to this website. Our website is not intended, however, to be used primarily an identification resource. Instead, there are many other sources of information on that aspect of reptile studies that we highly recommend in that regard. FIELD GUIDES Three that we recommend are: Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia, 2nd Ed , by J.C. Beane, A.L. Braswell, J.C. Mitchell, W.M. Palmer, and J.R. Harrison III; Universtiy of North Carolina Press, 2010. This book covers most of the reptile species found in our area, providing identification information, range maps, and details about habitats and life histories. Note that several taxonomic changes have occurred since this book's publication. Reptiles and Amphibians of the Smokies, by S.G. Tilley and J.E. Huheey; Great Smoky Mountains Association. Peterson Field Guide To Reptiles And Amphibians Eastern and Central North America, 4th Edition, R. Powell, R. Conant, and J.T. Collins; Mariner Books. WEBSITES There are now several websites that specialize in providing help with identifying reptiles: NC Museum of Natural Sciences, Herpetology Collection Amphibians and Reptiles of North Carolina TECHNICAL LITERATURE A vast amount of technical information on reptiles can now be searched for online. An incredibly useful resource is the Reptile Database. For older literature, an important resource is the Biodiversity Heritage Library. For more recent references, Google Scholar provides a way to locate articles on particular species or subjects. The primary technical reference for reptiles in North Carolina is: Reptiles of North Carolina, by William M. Palmer and Alvin L. Braswell; UNC Press, 1995 (reprinted in paperback 2013). This is the ultimate resource for complete information on the natural history and identification of North Carolina's reptiles. Although the taxonomy is out of date now for some taxa, it can be linked to updated taxonomy through our site. Much of the information on natural history and scalation comes from Palmer & Braswell's work. A number of major compilations have been written on the reptiles of North America. These include: Turtles of the United States and Canada. 2nd ed., by Carl Ernst and Jeffrey Lovich; Smithsonian Books, 2009. This book provides the most complete information on the snakes of North America, including their identification and taxonomy, distribution, and details about habitats and life histories. Snakes of the United States and Canada, by Carl Ernst and Evelyn Ernst; Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Like the Turtles of the United States and Canada, this book provides comprehensive information on the snakes of North America, including their identification and taxonomy, distribution, and details about habitats and life histories. SPECIMEN-BASED IDENTIFICATION If you are fortunate enough to live near a large reference collection, such as the Herpetology Collection at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, direct comparison of a specimen to those identified in the collection offers one of the most traditional means of determining an unknown species. NORTH CAROLINA HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY Joining the NC Herp Society is a great way to get involved with others interested in our state's amphibians and reptiles, and learning from them. |

General Reptile Ecology |

on the left, or to the next species in the checklist order by clicking on the Crotalus

on the left, or to the next species in the checklist order by clicking on the Crotalus  on the right. You can also get to additional species by entering text in either of the Search Common or Search Scientific boxes; click on the full species name; then click on the blue Find tab. A third way to get to another species (within the same Family) is to click the down arrow under the scientific name, where the box shows other members in the Family; click on the species of interest.

on the right. You can also get to additional species by entering text in either of the Search Common or Search Scientific boxes; click on the full species name; then click on the blue Find tab. A third way to get to another species (within the same Family) is to click the down arrow under the scientific name, where the box shows other members in the Family; click on the species of interest.