|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

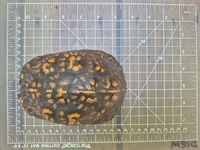

Photo Gallery for Terrapene carolina - Eastern Box Turtle

| 126 photos are available. Only the most recent 30 are shown.

|

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: Terrell Tucker

Moore Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Bischof

Transylvania Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Bischof

Transylvania Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Hutson

Cleveland Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Hutson

Cleveland Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Bischof

Transylvania Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: S. Tillotson

Burke Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: J. Mickey

Wilkes Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: R. Newman

Carteret Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: Matt Perry

Surry Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford, J. Plough, M. Boyd

Camden Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: J. Mickey

Surry Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: K. Sanford

Camden Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Bertie Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: D. DeHaven

Camden Co.

Comment: |

| Recorded by: K. Sanford

Camden Co.

Comment: |  | Recorded by: Alina Martin

Macon Co.

Comment: |

|

»

»

»

»