| SPIDERS |

|

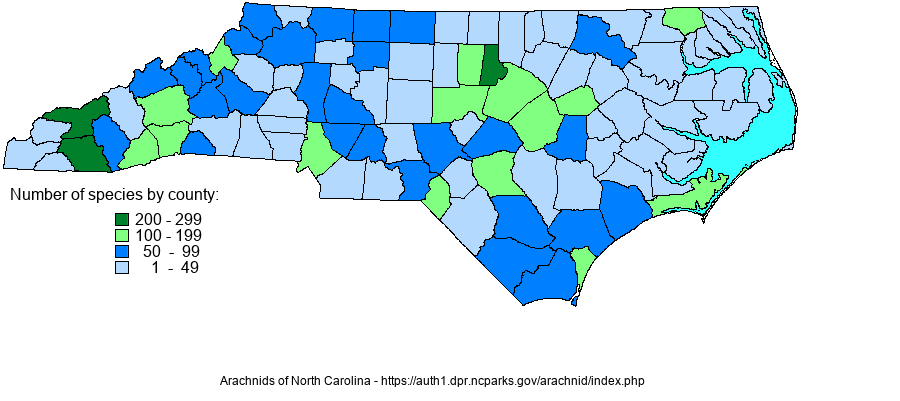

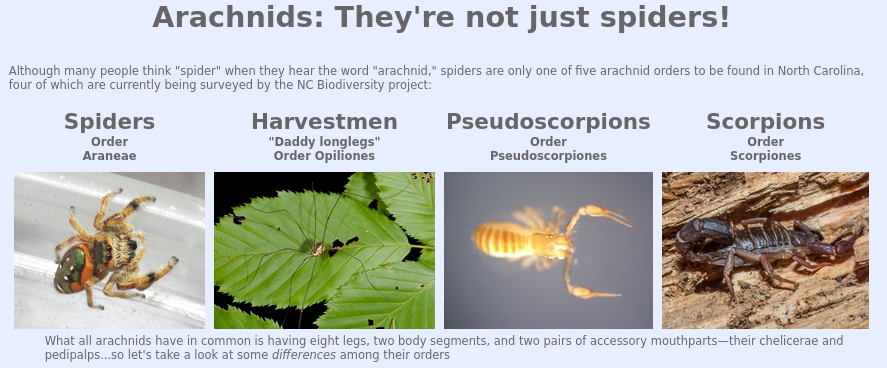

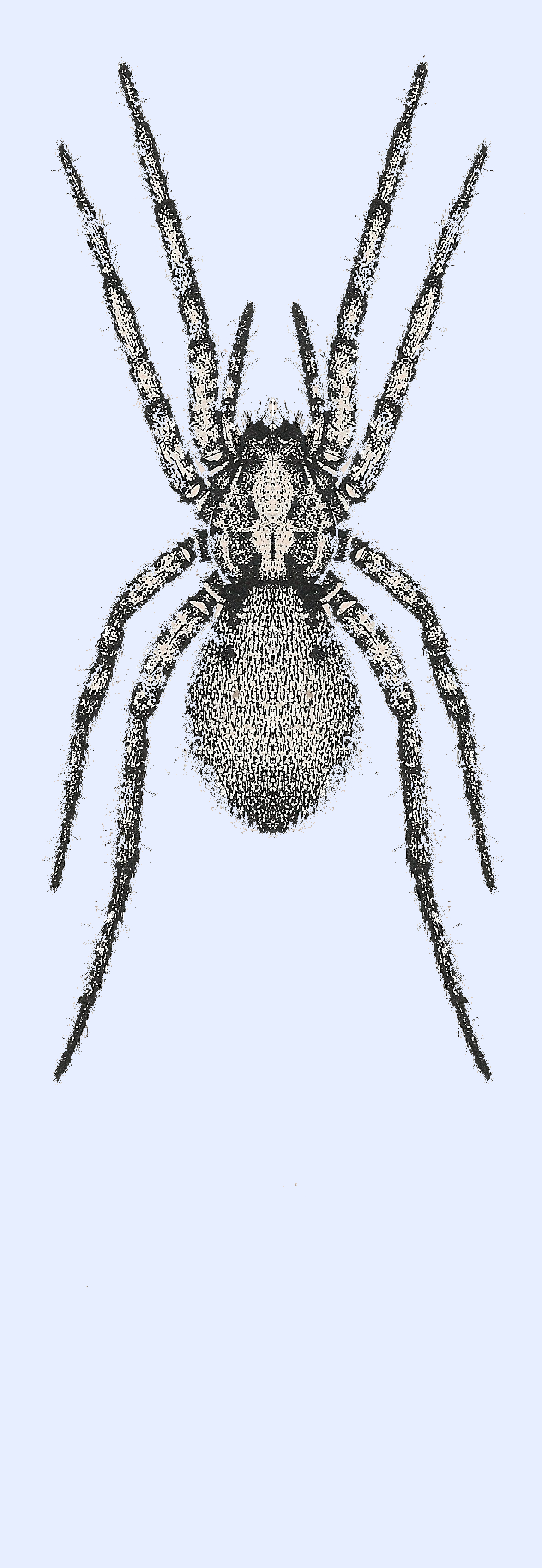

| Spiders are the most commonly seen and recognized among the four arachnid orders being surveyed by the NCBP, and are represented by nearly 700 species in our state. At this writing, there are more than 53,700 spider species in 139 families (including more than 6,900 species of jumping spiders!) that have been described and named worldwide, with more coming nearly every day! Check this page to see today's official count.)

The most readily obvious feature that sets spiders apart from the other arachnids is their ability to produce silk from abdominal spinnerets. All spiders produce such silk, using it in some combination of capturing prey, protecting their eggs, providing shelter, finding mates, and dispersing via airborne "ballooning."

Ca. 99.5% of known spider species produce venom which is used primarily for subduing prey, but which may also be used for defense. Fortunately, very few species have venom medically significant to humans; even those few that do are reluctant to bite, for unlike some insects that feed on human blood (e.g. mosquitoes, bedbugs, etc.), no spider has ever been known to do so.

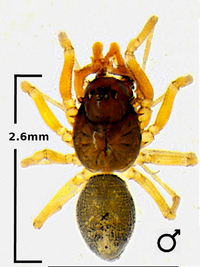

Adult spiders range in size from less than 1 mm (0.04 in.) to over 30 cm (over a foot, including their leg span), although Bradley (2013) points out that "Nearly half of the species in North America north of Mexico never grow to more than 3 mm (about an eighth of an inch) long." With the exception of Antarctica, they can be found on all continents, where some live on mountaintops, others in deserts; some live underwater in freshwater "diving bells," still others live in the ocean along shorelines and on coral reefs, only exposed to air during the lowest tides.

Among the nearly 700 spider species on the NCBP Checklist, are some that we can no longer find in our state, owing to habitat loss, climate change or other factors. At the same time, we are finding species new to NC, attributable to human movements of plants and goods and to our warming climate's becoming more hospitable to spiders previously found further south. |

|

For more information about spiders:

Bradley, Richard A. 2013. Common Spiders of North America. 1st Edition. University of California Press; Berkley & Los Angeles, California, USA. (Good for general ID and biology)

Platnick, Norman I. (ed.) 2020. Spiders of the World: A Natural History. Princeton University Press; Princeton, New Jersey, USA. (Good overview of worldwide families, great photos)

Rose, Sarah 2022. Spiders of North America. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ USA. (An excellent field guide with many photos and much biological information)

Ubick, D., Pacquin, P., Cushing, P.E. and Roth, V. (eds). 2017. Spiders of North America, An Identification Manual, 2nd Edition. American Arachnological Society, Keene, New Hampshire, USA.(Keys to genera, but rather technical)

|

PSEUDOSCORPIONS |

|

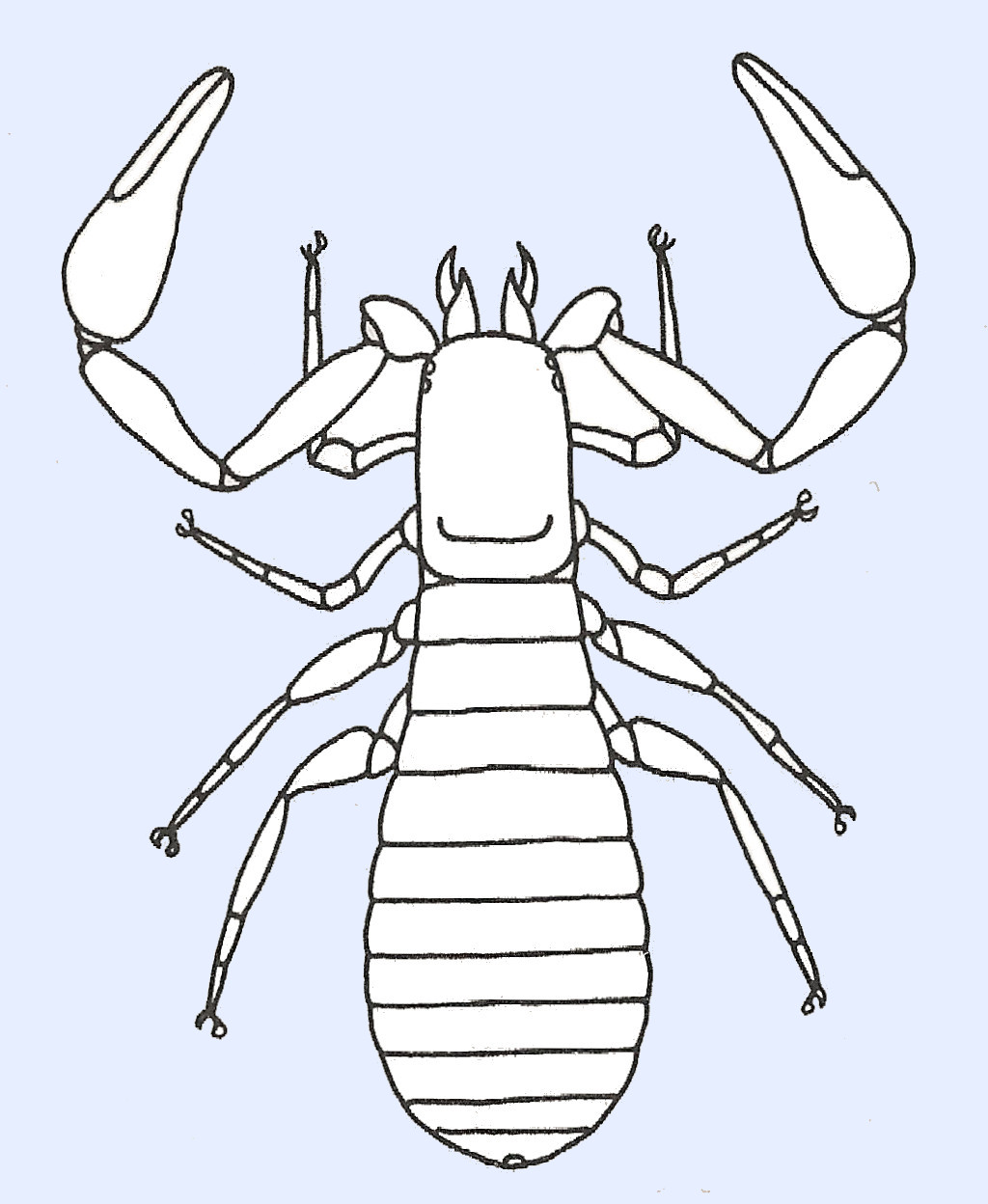

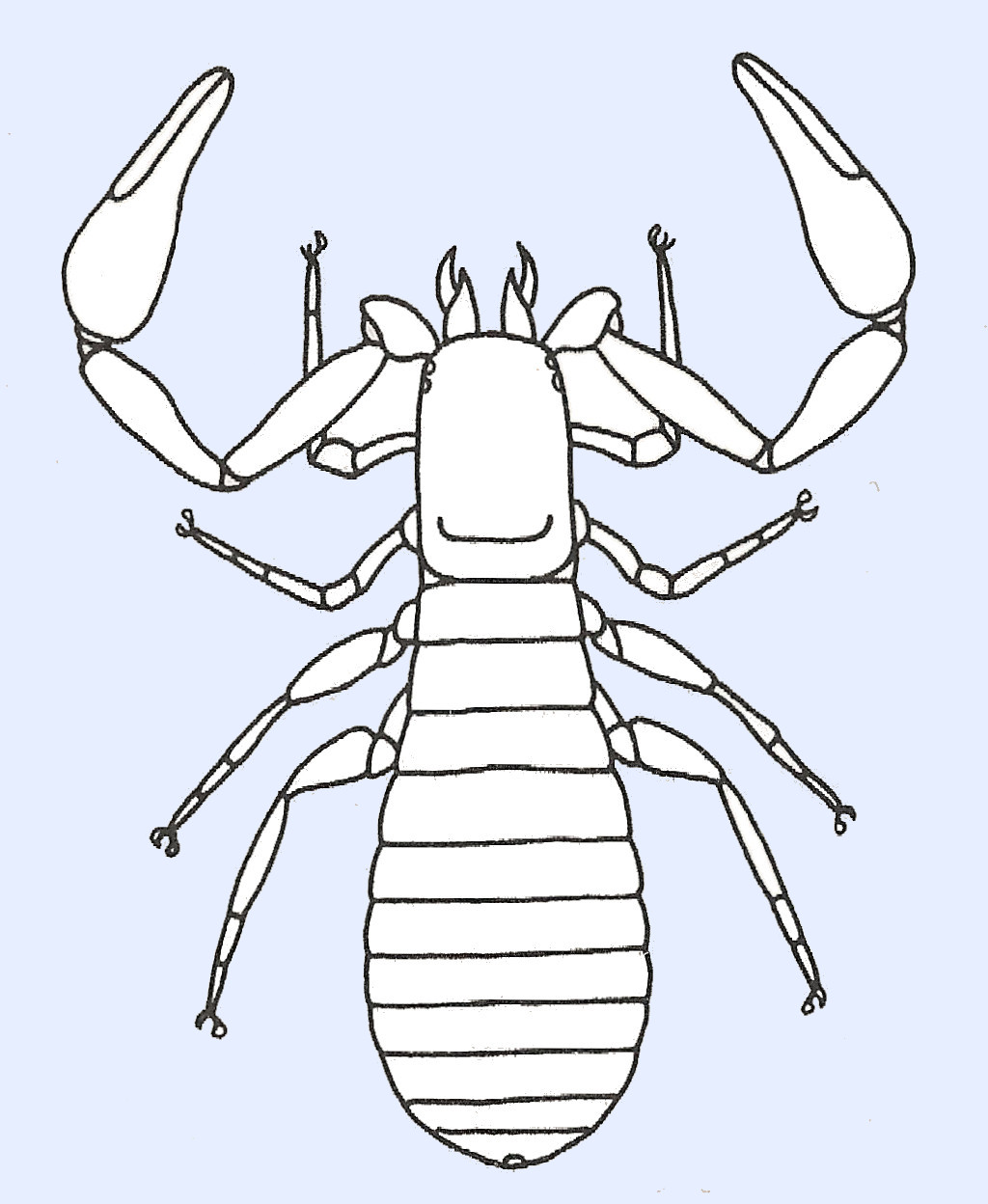

| Pseudoscorpions are a fascinating but poorly known group of arachnids. They are distributed widely but seldom seen because of their tiny size and secretive habits. They are predators, many with venom in their scorpion-like palpal fingers, but they are too tiny to pose any threat at all to people or domesticated animals. They have a distinctive appearance, but are challenging to identify to the species level.

Like other arachnids, the pseudoscorpion body is divided into a prosoma, or cephalothorax, and an opisthosoma, or abdomen. They have eight legs, plus large, specially adapted pedipalps with pincers that resemble those of a scorpion. The pseudoscorpion, however, has no stinging tail. At the front of their body is a pair of jaws called chelicerae, also with pincers, used to manipulate food and also to spin silk. The abdomen is divided into segments, and the overall color can be brown, black or reddish-brown.

Pseudoscorpions can be found in moist, sheltered places such as soil or leaf litter, rotten logs, under bark, in compost, and under stones. They feed on the numerous springtails and other tiny creatures in these habitats. Chelifer cancroides can be found in houses worldwide, feeding on book lice and other house-dwelling arthropods. Pseudoscorpions have also been found in bee hives, feeding on the parasitic Varroa mites, but not attacking the bees or their larvae or pupae.

Like many predators, pseudoscorpions have relatively small broods of young. Twenty to forty eggs are carried under the mother's abdomen, and the young ride along for a while after they hatch. To distribute themselves from place to place, tiny pseudoscorpions will use their pedipalps to grip on to the leg or body of a fly, beetle, or moth, and hitch a ride to a new home.

|

|

For more information about pseudoscorpions, see:

Harvey, M.S. (2011) Pseudoscorpions of the World:

http://www.museum.wa.gov.au/catalogues/pseudoscorpions

|

| SCORPIONS |

|

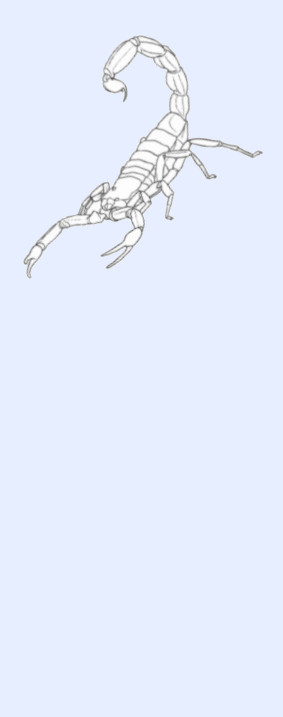

| Scorpions are an iconic group of arachnids. Their combination of claws (grasping pedipalps), eight legs, and elongate body with a segmented tail ending in a venomous spine is distinctive. Ancient astronomers were even able to discern the shape - Scorpio - among the stars.

Scorpions are found naturally on all major land masses except Antarctica and some island nations, e.g., United Kingdom, Japan, New Zealand. However, they have been accidentally introduced to most of the developed world by hitchhiking among agricultural products. At this writing, there are more than 2900 described species and subspecies.

While all species are venomous, only about 25 are known to have venom capable of killing a healthy human. The three species (1 native, 2 introduced) reported for NC have venom with low toxicity to humans. The venom is a neurotoxin and fast-acting. However, most often scorpions kill their prey by crushing with their pedipalps.

All scorpions are predatory, mainly capturing small invertebrates. They are nocturnal, spending the day in holes or undersides of rocks, and emerging at night to hunt and feed. While their eyes (6 to 12 depending on species) are unable to form sharp images, they are extremely sensitive in low light conditions - able to navigate at night using star light. Their body is very sensitive to vibration; often determining prey direction and range by "feel".

Reproduction involves a complex courtship ritual prior to mating. All scorpions give birth to live young ranging in number from two to over a hundred depending on species and environmental conditions; the female having carried the fertilized eggs internally.

Scorpion venom is of medical interest. Toxins from a number of species are being investigated for treatment of autoimmune disorders, certain cancers, and as anti-malarial drugs.

The scorpion exoskeleton will glow a vibrant blue-green when illuminated by a black light (UV). One study suggests that this sensitivity to UV might help the scorpion hide better at night.

|

|

For more information about scorpions, see:

The Scorpion Files. An extremely thorough compilation of all things scorpion, created and maintained by Jan Ove Rein, M.Sc.

Kovarík, František (2009). "Illustrated catalog of scorpions, Part I" (PDF).

Gaffin, Douglas D. et al. 2012. "Scorpion fluorescence and reaction to light". Animal Behaviour 83 (2012) 429-436.

Wikipedia: Scorpion Morphology

|