|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recording Gallery for Pseudacris brimleyi - Brimley's Chorus Frog |

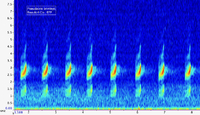

| 2022-02-17. Beaufort Co. Jim Petranka and Becky Elkin - 5-6 calling from swamp and opening immediately next to swamp. |

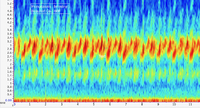

| 2022-02-17. Washington Co. Jim Petranka and Becky Elkin - Several calling from area with Phragmites (?) - tall, robust aquatic. |

| 2022-02-17. Beaufort Co. Jim Petranka and Becky Elkin - Only two adults were heard calling from a shallow roadside ditch. |

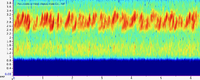

| 2022-02-17. Hyde Co. Jim Petranka and Becky Elkin - A chorus of 15-20 or so were calling from a pocosin; 11:40 AM; air temp = 70F. |

»

»